In defense of the .zip TLD

I recently released a small (infinite) word game which had the pleasure of getting some good exposure from Gizmodo in this article:

The headline suggests my wholesome game is a wasteland of phallic imagery… but any publicity is good publicity! I was very happy with the (indecent) exposure, and got a decent bump in traffic as a result.

There was, however, a paragraph which I took personal affront to:

It’s also notable for using the .zip domain, which—despite what one might assume—is not exclusively for phishing attacks based around fooling people who believe they’re downloading a .zip file (see: when Google opened registrations for the domain in 2023, multiple security researchers and companies condemned the idea, warning that people generally associate “.zip” with a file type, not a top level domain).

Now I might not be the most unbiased person to voice my opinion here, I happen to have a small horde of .zip domains; monkeys.zip, words.zip, hn.zip and my personal site that you’re currently on… but I would like to get a chance to defend my choice.

When the .zip TLD was opened back in 2023, it was indeed met with widespread disdain from a number of Web Security researchers & bloggers. It quickly became common wisdom that zip websites were dangerous - and that in no time, a flood of new phishing scams will spread chaos throughout the internet.

Well it’s 2026 now, so let’s talk about it. What’s the big deal with .zip domains?

Argument #1 - You can be linked to something you didn’t expect

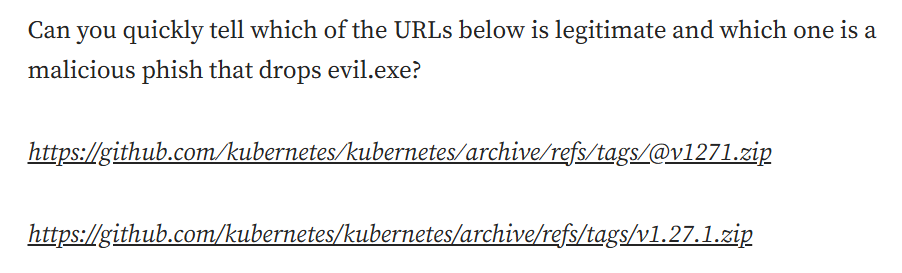

The most frequently referenced source for why .zip is bad is this article from Bobby Rauch. The author shows off a new attack where one can click a link expecting to arrive at one place, and instead arrive at another:

This is a very clever demo, using some esoteric URL knowledge that can deceive even technical users. The trick involves sneaking in an ’@’ symbol into the URL, and a handful of fake unicode forward slashes - so that even though the URL starts with ‘github.com’ - the link actually points to v1271.zip. This site downloads a nasty virus and now you’re SCREWED!

But before we condemn .zip domains as a result of this creative demo, let’s think about how this attack would work in practice, and if the .zip TLD is responsible for it.

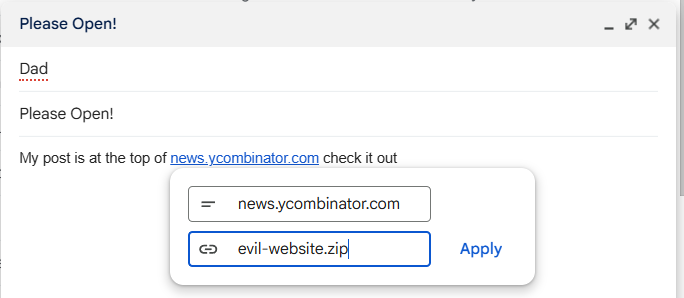

If a malicious person wants to make a deceptive link, there’s a much, much easier way than with unicode trickery. For example, just follow this link to Wikipedia https://wikipedia.org/wiki/Phishing to see for yourself! On the web, we can make links say anything - it’s been a feature of HTML for 30+ years, and is likewise available in email clients or anywhere markdown is supported. The author argues that especially in an email client, our clever villain may “change the size of the @ operator to a size 1 font, [making it] visually non-existent for the user, but still present as part of the URL”… but how about this little trick?

Argument #2 - .zip is a file extension and file extensions shouldn’t be TLDs

The argument here is that domain names have their own world, file names have theirs, and never the twain shall meet - you can find an example of this thinking in this article:

Domain names and filenames are not the same thing, not even close, but both of them play an important role in modern cyberattacks, and correctly identifying them has formed part of lots of basic security advice for a long, long time.

First, I disagree that the distinction between domain names and filenames is inherently relevant to security. I also think the suggestion that “both of them play an important role in modern cyberattacks” is a nearly tautological statement - every aspect of computing is relevant to cyberattacks!

But more importantly, there has never been an explicit or implicit rule that these two worlds cannot overlap. In fact, you may be surprised to learn that our sacred ‘.com’ TLD was a widely used executable file extension for decades, and some modern software uses it as well. There’s plenty of other examples as well - ai is used by Adobe Illustrator, .app is the extension of MacOS packages. Poland’s .pl is used for Perl scripts, and Saint Helena’s .sh is commonly used for shell scripts. Besides tradition, I don’t see any reason ‘.zip’ is too precious to preserve.

It seems to me that the cat is out of the bag on TLDs colliding with filename extensions, and has been for a while. The best security advice is to be suspicious of ALL links - not tempering our suspicion based on the TLD. Let’s also not instill fearmonger users into avoiding .zip URLs altogether, thereby driving them away from my precious monkeys.

Argument #3 - unintentional linkification

This is by far the most interesting one for sure - and funnily enough, it’s the one least referenced in popular articles and blog posts.

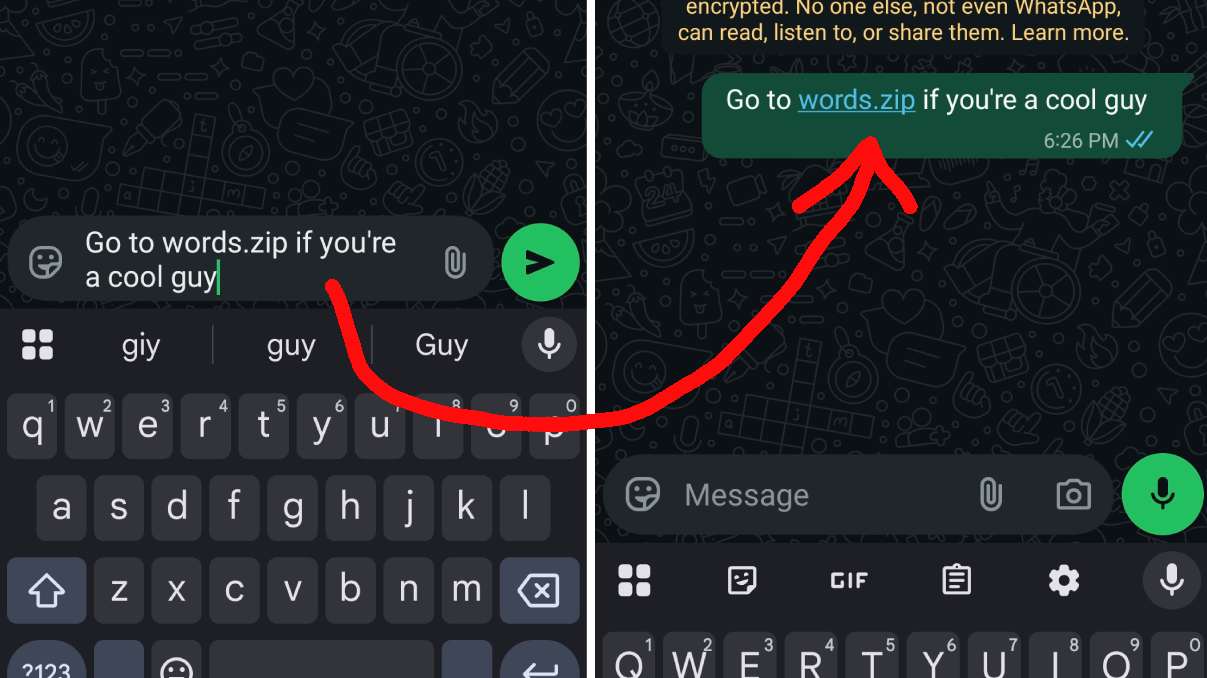

A lot of web apps and software will automatically ‘linkify’ any user submitted text that looks like it could be a link, so when you write “go to google.com” - the text editor swaps in “go to google.com”.

So if a malicious actor gets a domain that sounds like a common zip file - this could open up an attack where you try to tell your friend “hey I sent weddingpictures.zip to your email” and your friend clicks the resulting link, thereby being redirected to a trick site that steals your SSN.

I actually think there’s merit to this idea, however I haven’t seen a single live example of this attack, nor do I suspect there has been. There’s been a few ‘I told you so’ articles about .zip sites being used for phishing, but as far as I can tell, they’re just phishing sites that use .zip not for the association with the archive format, but because it was cheap to buy ‘microsoft.zip’. But this is a problem for any new TLD, as every large brand is compelled to have their domain in every TLD, otherwise someone winds up with facebook.sucks and makes a stink of things.

But, back to linkification - I actually think it’s a broader issue - and that the user should be in greater control on whether they want to link to something or not. I initially doubted this would be a problem, but check out this brief survey of platforms, and what happens when I input either “https://luke.zip” or “luke.zip” into them, and if I can edit/remove this link before submitting.

| Platform | https://luke.zip | luke.zip | removable |

|---|---|---|---|

| discord | YES | NO | YES |

| YES | NO | YES | |

| google docs | YES | NO | YES |

| gmail | YES | NO | NO |

| YES | YES | NO | |

| YES | YES | NO |

While most do not automatically linkify ‘luke.zip’ - Twitter and WhatsApp do - this isn’t so bad. What is worse is that on these platforms you CANNOT remove the link! There is no ability to say “I don’t want to add a link here, DON’T make this text a link please.

This is annoying, and I think it should be fixed… but I still don’t believe anyone is clicking zip files in tweets and getting phished. They’re certainly not clicking any of mine at least, but that’s probably because I have like 20 followers and hardly tweet anything.

Anyway! What do you think? Should I swap all my domains to be .mov instead?